For a technical introduction to MEV post-merge, check out our earlier report.

The Tie Research

MEV: The Censorship Dilemma

The State of MEV Censorship

Not all validators explicitly and purposefully propose blocks built by MEV relays. Many propose vanilla blocks–or blocks selected from the mempool without overt consideration of ordering, and purely based on priority fees and block limits.

For instance, Coinbase, the largest centralized staking provider outside of Lido, has only recently begun incorporating MEV into a minority of their proposed blocks. Over half of Kraken’s proposed blocks, on the other hand, have been explicitly ordered. By doing so, Kraken has definitionally earned more staking rewards than Coinbase on a rate basis. Why would Coinbase forgo this extra yield? Is Kraken taking on additional risk?

Validators consider several variables when choosing an MEV relay. There are, however, two chief considerations:

- Are there transactions in the block from OFAC sanctioned addresses, and,

- Does the MEV relay facilitate frontrunning?

Respectively, a validator weighs these variables through a combination of compliance and profitability.

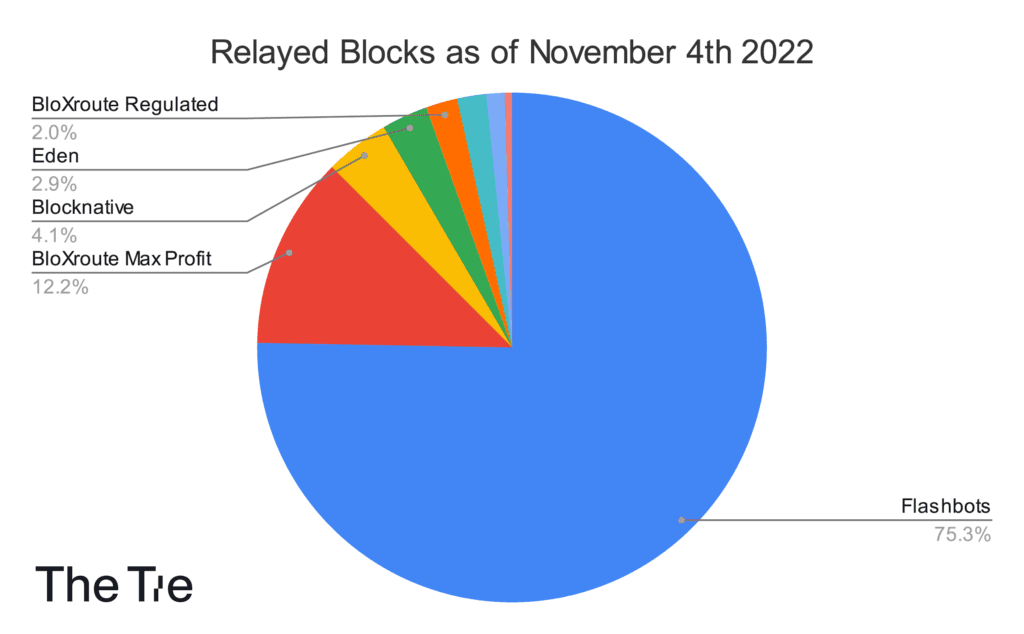

For an example, take BloXroute Max Profit- the only MEV relay that strictly prioritizes profitability. As shown in the chart below, this relay only represents 12.2% of all relayed transactions, suggesting that most validators do not have the sole aim of profitability.

Below we show the current distribution of relayed blocks on Ethereum since The Merge.

Flashbots has relayed over 75% of Ethereum blocks known to be explicitly ordered since Ethereum’s transition to Proof of Stake. From a decentralization standpoint this is obviously not ideal, but this market share has recently normalized. Previously, we had identified three such similar vectors for post-merge centralization.

Clearly, we’re dealing with a pair of subjective tradeoffs. For instance, centralized exchanges are legally required to choose relays enforcing the OFAC blacklist. Moreover, any entity staking Ether on another’s behalf, centralized or decentralized, is financially obligated to propose blocks from a relay that incorporates frontrunning. That is to say, fiduciary responsibility requires the most profitable block be proposed.

Only a solo validator, a user with sole discretion over their Ether staking rewards, is capable of choosing a relay that neither adheres to the OFAC blacklist, nor proposes blocks that incorporate frontrunning of the mempool. This is not to suggest frontrunning is unethical. We’re simply stating that solo node operators are the only participants strategically enabled to forgo both aforementioned considerations, and pursue the BloXroute Ethical relay.

Both of these variables (compliance and profitability) have considerable impact on the Ethereum MEV landscape. For instance, if an OFAC sanctioned address submits a transaction with a high priority fee, validators that choose to incorporate such transactions will necessarily benefit financially. Because validators' proposals are random, we know a validator subscribing to a OFAC agnostic relay will eventually have the ability to propose a block containing non-compliant transactions, as long as it is maintained in the mempool.

Similarly, frontrunning, sandwiching, arbitrage, and other forms of transaction ordering provide more efficient price discovery on the blockchain, allowing MEV enabled operators to earn higher yields.

However, something interesting occurs when looking at the average block value of relayed blocks- BloXroute Max Profit relay earns the same as their Regulated relay. On paper, this shouldn’t check out, given that excluding blacklisted addresses can only negatively impact priority fee ordering.

Ordering Strategies & Block Value

To understand why ‘Average Block Value’ doesn’t necessarily represent the most profitable relay strategy, we must first clarify two things.

First, we must recognize the economies of scale inherent to MEV relays. If a relay is proposing a certain percentage of blocks, at some level they’re able to calculate their likelihood of building the subsequent block. Successfully building two blocks in a row gives a relay additional opportunities for MEV.

Let’s rephrase that in a different way: if the Flashbots relay builds the most profitable block for the proposing validator, and they know their likelihood of building the next block in the chain, it will influence the original and subsequent block’s composition. However, as Flashbots’ builder dominance has dropped, their likelihood of winning successive blocks has fallen with it, rendering it extremely unlikely.

Second, we must understand how relays are technically selected. Depending on the smartnode stack used to deploy a node, a validator may be able to rank order their preferred relays. Nothing prohibits this. In such a case, a validator could always utilize the most profitable relay. An Ethereum validator that happens to earn a block proposal is capable of mandating that block be submitted by the most profitable relay.

With this in mind, and from a statistical perspective, the observed ‘Average Block Value’ cannot necessarily represent the most profitable relay strategy, regardless of sample size. For instance, how is it that block values proposed via the ‘BloXroute Max Profit’ relay are often less than the block values proposed by the ‘BloXroute Regulated’ fork? From Table 1 we know this shouldn’t be possible.

A practical example makes this clear:

A staking pool, in its entirety, has only whitelisted Flashbots and BloXroute Regulated relays. By definition, the validator from the pool in question will only choose a block from the BloXroute Regulated Relay if it is more profitable than the the proposed Flashbots relay--this validator is not considering blocks built by other relays, and we know an MEV ordered block is necessarily more profitable than a normal, fee ordered block.

Due to varying ordering strategies, irrespective of blacklist and frontrunning mandates, the BloXroute Regulated Relay, if chosen as the backup proposer to a major pool, could easily average higher block rewards than an unrestricted BloXroute Relay.

Censorship

Previously I’d stated Flashbots alone, a censoring relay, accounts for over 80% of all relayed transactions. It’s important to keep in mind that not all validators are outsourcing their block building to MEV relays, and many still propose vanilla blocks, or blocks locally ordered. As of December 14th, around 70% of all proposed blocks were being routed through MEV relays enforcing OFAC censorship.

After withdrawals are enabled in the upcoming Shanghai upgrade, a reshuffling of staked Eth could bring this number down considerably.

How many transactions are actually being censored on Ethereum, right now? Given we know the number of proposed blocks being routed through OFAC compliant relays, the only additional information we need is average block time, and we know there is a new Ethereum block precisely every 12 seconds.

We can do some basic math to calculate the likelihood of a non-compliant transaction being included in a block, and then project that out to any number of blocks being added to the chain.

C = Percent of proposed blocks that are OFAC compliant.

B = Number of blocks into the future

Y = Likelihood of a censored block being included after a given number of blocks

Y = 1 - (C^B)

30% of the time a censored transaction goes through in one block.

51% of the time a censored transaction goes through in two blocks.

97% of the time a censored transaction goes through in 10 blocks.

As stated previously, we know 10 blocks = 120 seconds.

Therefore, even if over 90% of validators routed transactions through an MEV censoring relay, a non-compliant transaction would reach finality within an hour. That is also assuming the user does not include a higher than average priority fee; a sufficiently high priority fee would ensure inclusion in the next block, most of the time.

SAUVE - A Solution?

At Devcon, Flashbots teased an answer to these censorship concerns with a new version of their relay: Single Auction Unifying Value Expression (SAUVE).

SAUVE is decentralized, open source, and has an encrypted mempool, meaning transactions retain some level of opacity. MEV relays would be able to dynamically calculate ordered extractable value from the mempool without knowing the precise content of the transaction, thus giving them plausible deniability when including any censored transactions.

The status of a token remains unknown, but likely, as it would otherwise be difficult to properly decentralize the protocol. It is possible they simply present the solution as a public good, and forsake any form of monetization. Flashbots currently doesn’t monetize MEV-Boost, has open sourced all the code for their relay, and very recently open sourced their code for their block builder as well.

Flashbots is attempting to build and deploy this solution as soon as possible, although there haven’t been additional details since Devcon. There are technical solutions being proposed at Ethereum’s protocol level that could circumvent this problem entirely, significantly diminishing Flashbots’ role in the Ethereum ecosystem.

It’s likely some version of SAUVE would be incorporated into all or most of the relays. As it stands, most of the most popular relays, those referenced in Table 1, share the same code base. Flashbots first response to censorship concerns was to open source their code, allowing BloXroute and Eden to quickly develop.

In the short term, and while working on SAUVE, Flashbots is trying to ameliorate the problem in other ways. Recently, Flashbots released a new parameter called ‘min-bid’. This feature allows validators to set a minimum value threshold at which they will ignore MEV proposed blocks, and simply build locally. The idea being a validator can still catch the occasional ultra profitable MEV proposal, without enabling censorship just to be slightly more profitable.

As we know, the value of a proposed block varies drastically. Some are barely more profitable than a vanilla block, others can award you dozens of Eth! By playing with this ‘min-bid’ threshold, validators are now able to choose a specific price for which they’re willing to be OFAC compliant.

crLists & PBS enshrinement

Censorship resistant lists (crLists) would make it possible to force block builders to include transactions in a given block, else attestors must reject it. Proposal Builder Separation (PBS) would force proposers (validators) to use blocks built by builders, rather than build their own locally.

Combining and enshrining both of these upgrades at the protocol level would seriously inhibit a relay’s ability to obfuscate specific transactions. Any future upgrade would likely incorporate both of these upgrades in the same fork, rather than just one. PBS without crLists, for example, would actually make censorship worse.

Under a crList model, proposers would aggregate transactions that are likely being censored. The criteria are simple: find the transactions that have offered sufficient gas, are otherwise valid, and have been ignored for a statistically significant number of blocks. If a proposer builds a block without maxing out the block limit, they must include as many of the transactions on the crList as possible.

This report is for informational purposes only and is not investment or trading advice. The views and opinions expressed in this report are exclusively those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of The TIE Inc. The Author may be holding the cryptocurrencies or using the strategies mentioned in this report. You are fully responsible for any decisions you make; the TIE Inc. is not liable for any loss or damage caused by reliance on information provided. For investment advice, please consult a registered investment advisor

Sign up to receive an email when we release a new post